Episode 1. Once a month, we invite you to read about the singular experiences of jazz players heading back to their African roots.

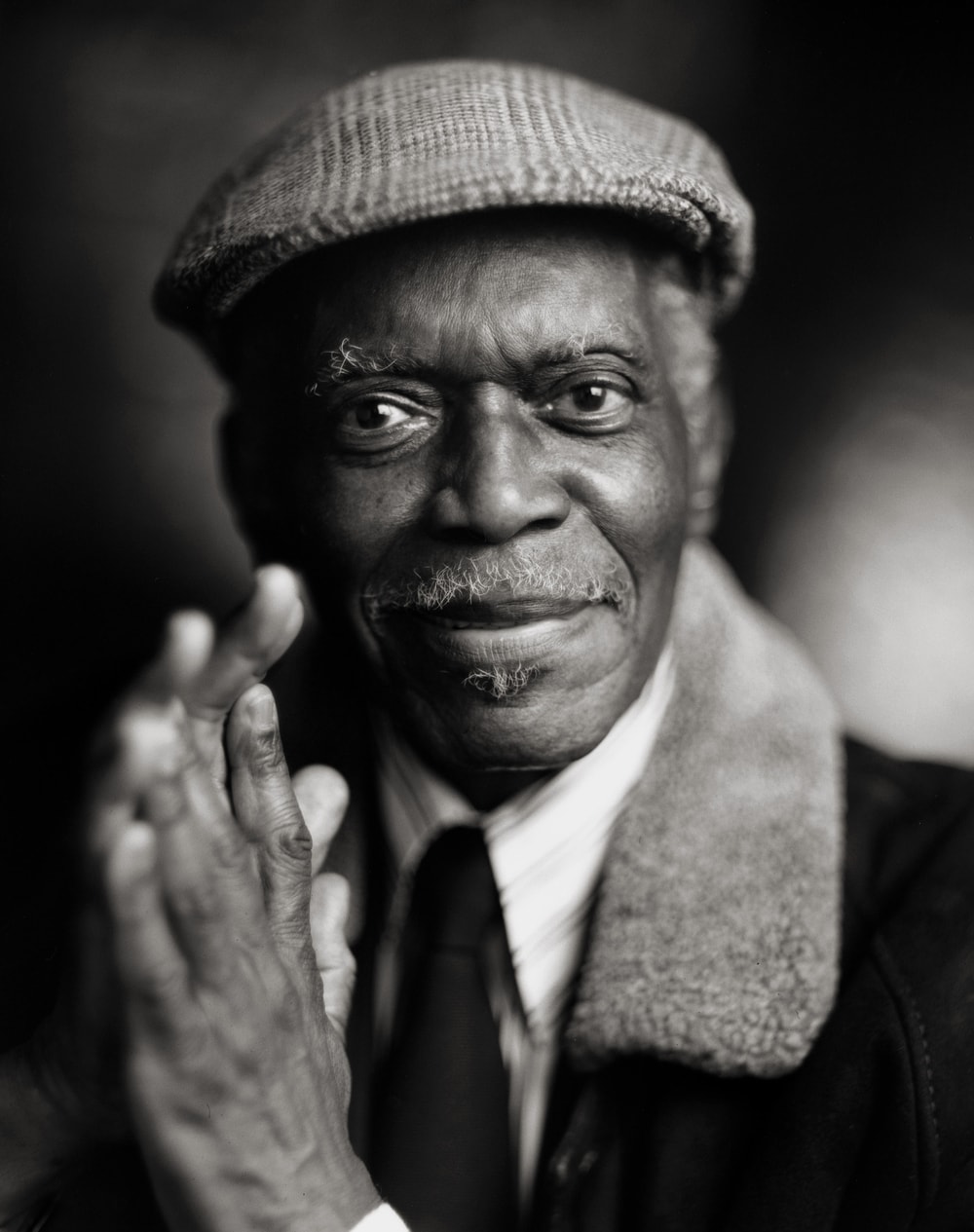

In the summer of 1993 when the American jazz pianist Hank Jones – a leading authority on the great tradition of jazz, at the age of seventy-five – expressed the desire to record an album of West African music, the project was met with a great deal of skepticism. This, however, was Jones’s main priority for he knew that time was short. Jean-Philippe Allard and Daniel Richard, producers of the label Polygram Jazz, complied with his wishes and quickly organised an appointment with Cheick Tidiane Seck, a keyboard player from Mali. Seck, a frequent visitor to the lands of black American music, seemed to be the connection that Jones – who believed that the Dogon region was the home of his ancestors – needed.

Seck, some ten years later, recalls that, ‘In fact, I didn’t even know the name Hank Jones. So I called Joe Zawinul, my older brother, who immediately told me it was a fantastic opportunity!’ Seck, from his first meeting with Jones, was in awe, ‘High class. He inspired respect and breathed life. In the lobby of the hotel where we met, there was a grand piano and he invited me to play a song. I chose “Kaira”, a Mandinka classic where I transposed a kora piece to the keys. Hank jumped up and said, “I’ve never heard anything like it! That’s exactly what I want to do!”’ And the rest is history!

A native of Segou and settled in Paris since 1985, Seck was in the perfect position to bring about a happy ending to this story, as he had access to a wide range of musical styles within the sub-continent. He had a handle on the traditional – thanks to his mother – as well as a more funky style, being a disciple of Jimmy Smith. Seck has greatly contributed the style’s evolution since the 70s, most notably with the Super Rail Band. Suffice to say that this ‘Warrior’, or ‘Black Buddha’ as he is known, quickly established himself as the man of the hour, with the dual missions of recruiting musicians from West Africa – his ‘Black Guard’ (Moriba Koïta, Kasse Mady Diabate, Djeli Conda Moussa, Kouyaté Lansiné, Tom Diakité, Mama Keita…and even the singer Amina) and of creating a bespoke repertoire for an American audience.

The whole project took about 8 months, with Jones ‘the old lion of Detroit’ making his mark from a distance. Seck, recalls ‘He called me from all corners of the globe, wherever he was playing, to tell me that he’d learnt something! And then he arrived in Paris to record. During the sessions he kept joking, playing the bits that grabbed him for the n’goni or the balafon with his right hand. He would show me stuff at the piano, I’d give him ideas at the Hammond organ. It was a thrilling exchange that gave me the confidence I was missing. The whole process was a great lesson in humanity and authenticity. At the end, he hugged me. He was very moved, as were we all. We felt that we had recorded an anthology, simply for the pleasure of this quirky gentleman.’ All done with immense talent, with the greats, a veritable ‘who’s who’ of jazz.

Jones chose to enter The Mandinkas’ groove without breaking in, proceeding with delicate touches, applying his knowledge of harmonics sparingly, to emphasise the melodic beauty of each piece. He creates harmony between balafon, guitar, and kora, and then blends in a perfect chorus. Alongside and with his fellow musicians, Jones was more than a leader – he took on the position of guest of honour. The perfect position in which to be open to new experiences, all the while passing on his wisdom to the youth. The perfect melding between the Mississippi Delta native and his distant cousin, rocked by the Niger River. The centuries, dividing oceans, oppression and colonisation have not been able to erase the memory of a common language, the blues.

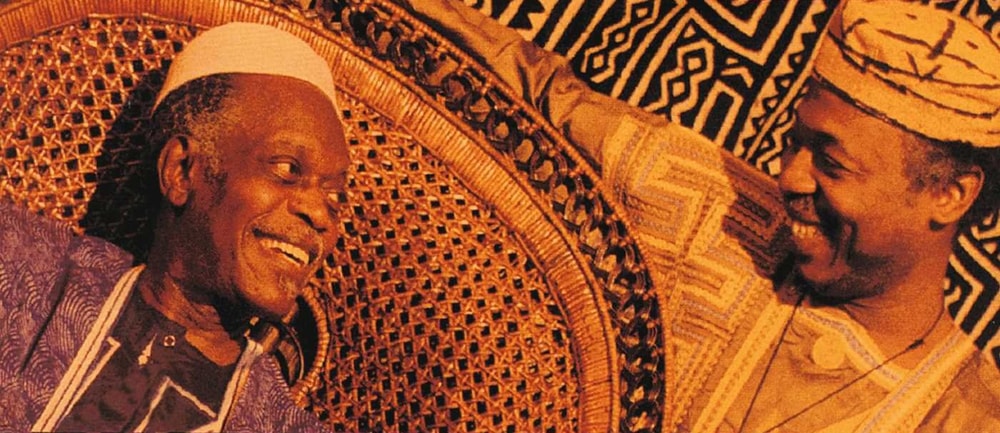

On the album cover, Hank Jones and Cheick Tidiane Seck smile broadly at one another. The perfect illustration of the relationship which transformed what could have been a mere project, into a precious object. ‘Mamadou the charming, what are the customs of these places? Can you inform me because I am a stranger? Guide our steps because we are adventurers …’ After a short introduction on the Fulani flute from the totemic Aly Wagué, the words of Seck guide Jones through the empire of sound and meaning that is Mali. The choice of the track “Sarala” – a Bambara melody that swarmed throughout the Mandé and has been reinvented within the folds of present-day afro-jazz – was no accident. Sarala, like saravah in Brazilian, must be listened to as salvation, a blessing, ‘it is advice to be careful and respectful so as to avoid the pitfalls of navigating a new world. This sums up Jones’ spirit – a musician who knew everything about jazz, had over 800 records, and yet came to us with wisdom and humility’ remembered the Malian in July 2010, with a tear in his eye. A month and a half earlier, the oldest Jones brother (Elvin a drummer for Coltrane, and Thad a great conductor) passed away at the age of 91, and with him went the possibility of recording a sequel to this first album, which has become – as if by magic – a classic. The two friends had just enough time to take to the stage together, in September 2009 at Jazz in La Villette. Alas, it would be for the last time.

While the album is the culmination of a dream, the pianist never did walk on the land of his ancestors. ‘Everyone held hopes of him for many years,’ recalls Seck referring to the roaring success of the album even before it was officially released. ‘Radio Mali has not stopped playing it ever since. This album is even more famous than I, The Warrior! It has received critical acclaim from the likes of Oumou Sangaré or Toumani Diabaté. This album is a miracle, a gift from the Gods.’

Listen to Sarala on Spotify, Deezer or Apple Music.

Jacques Denis is on Twitter.